It turns out that the ways we write and speak have changed some since the textbooks were written. Case in point.

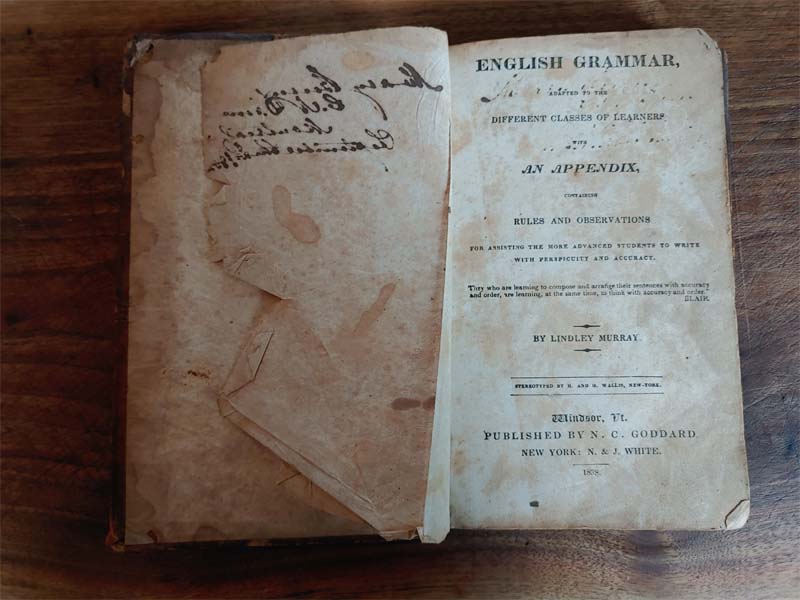

My friend Emery gave me an English grammar “Rules and Observations” book published in 1838. The inside cover page of the book reveals that it is intended “for assisting advanced students to write with perspicuity and accuracy.”

It is a beautiful old book, with a scuffed hard cover, yellowed pages that have that wonderful old book smell, and it’s pocket-sized for all your on-the-go grammar emergencies. I have to very gently turn the brittle pages in order to avoid damaging them.

Emery and her husband David run the wondrous, delightful, must-visit Bird and Bee vintage shop at the Wincey Mills in Paris, Ontario. That is where my ancient grammarian is from.

See what I did there? Several different grammar mistakes in a rather short sentence. A grammarian is a person – a grammar expert – and not a book. Also, dating back to 1838 isn’t long enough to qualify the volume as ‘ancient.’ It’s merely old.

Actually, in the preceding few paragraphs, I’ve made quite a few other grammatical errors as well. However, this is how I write. It’s how many of us write, and despite the good intentions of the well-meaning folks of 1838, I think we can still come across as perspicuous and accurate while flouting many of their grammatical conventions. For example: “Two different grammar mistakes in a rather short sentence.” It does not contain a predicate. There is no verb to speak of.

Actually, in the preceding few paragraphs, I’ve made quite a few other grammatical errors as well. However, this is how I write. It’s how many of us write, and despite the good intentions of the well-meaning folks of 1838, I think we can still come across as perspicuous and accurate while flouting many of their grammatical conventions. For example: “Two different grammar mistakes in a rather short sentence.” It does not contain a predicate. There is no verb to speak of.

Five classic grammar rules it’s more than okay to break now

Never end a sentence with a preposition. Sticklers will often point out this rule to novice writers. It is true that there are times when a sentence can be improved by rearranging it so that it does not end with preposition. However, in many cases, ending with a preposition is not only fine, but it is actually preferable.

For example, saying “I have no one to dance with” is perfectly okay. Reordering the sentence so that the preposition does not fall at the end would come across as overly stiff and frankly outdated. “I have no one with whom to dance.”

You won’t be interviewed for every job you apply for.

vs.

You will not be interviewed for every job to which you apply.

And don’t begin a sentence with a conjunction. But Peter, you insist, surely you can’t break that rule. Your grade five teacher was adamant about not starting sentences with conjunctions. And that may be true, but no matter how steadfast they were at the time, what they so emphatically told you is no longer correct.

Because the way we use language has evolved over the years – since 1883, certainly, but also since 1987, or whenever you were in grade five – it is now perfectly acceptable to open a sentence with your favourite conjunction. So, go ahead.

The singular use of they or their. Notice how when I referred to your elementary school teacher, I said they were wrong? Traditionally, one would have written something along the lines of “as for your teacher, he or she was mistaken.” In many cases, people were even taught to default to the ‘he’ for individuals of a crowd that contained both males and females. Naturally, people don’t like that so much and more.

But even the ‘his or her’ become cumbersome. “Each student must bring his or her application to his or her appointment.” It is far easier – and now commonly accepted – to simply write: “Each student must bring their application form to their appointment.”

Be sure to never split your infinitives. Once again, it is true that there are many times when a sentence can be improved by avoiding a split infinitive. (Separating the word ‘to’ from the verb that follows.)

I just need to quickly finish this versus I just need to finish this quickly.

In many cases, however, the split infinitive actually sounds stronger than the more classically grammatically correct option.

Just ask Star Trek. Does it sound more powerful to go boldly where no one has before or “… to boldly go where no one has before.”

No sentence fragments, please. Every proper sentence needs a subject and a predicate, of course. Except when they don’t. In writing that has evolved to mirror natural language use and a more conversational style, a sentence fragment is often the most efficient way to express a thought. It can also be a powerful way to emphasize a particular thought among longer, more complex sentences. In such cases the subject or verb can be naturally assumed from the context of the previous or following sentences. We give our readers the benefit of the doubt. They can follow along just fine.

“While it seemed like the odds were stacked against the local players, they would not accept defeat. Not this team. Not today. In the third period… ”

Bottom line. Language evolves and usage is fluid. Write in the style of today. And once you’ve mastered that, write in your own style.

Oh, and while we are on the subject of updating the rules, here is a piece I wrote for one of our clients on how it is totally no longer necessary to leave two spaces after a period when typing. So, stop it now.

Here is one final note from the English grammar book from 1838. In the introduction, the author acknowledges, “works of this nature admit of repeated improvements; and are, perhaps, never complete…”

We’re all a work in progress.